18.1. Making a perfect cappuccino#

Specific heat versus heat of vaporization

| Author: | Frits Hidden, Jorn Boomsma, Anton Schins, Ed van den Berg |

| Time: | 10 - 15 minutes, more if student computation work is integrated in the demo |

| Age group: | 14 - 18 |

| Concepts: | Heat of vaporization and condensation, specific heat |

This demonstration has been published by the authors in Hidden et al. [2012].

Introduction#

A cup of cappuccino is prepared by adding about 50 mL frothing, foaming milk to a cup of espresso. Whole milk is best for foaming and the ideal milk temperature when adding it to the espresso is 65°C. The espresso itself may be warmer than that. Moreover, during the heating, the milk should not burn as that would spoil the taste. The best way is to heat the milk slowly while stirring the milk to froth and create foam. However, in restaurants they do not have time for slow heating. Could we heat the milk by just adding hot water?

Fig. 18.1 The context of this demonstration: A cappuccino#

This question can be posed to your students first.

Exercise 18.1

How many mL of 90°C hot water would be needed to heat 50 mL of milk from refrigerator temperature (say 4°C) to 65°C? Assume that the specific heat of milk is the same as the specific heat of water.

Students answer the question on a worksheet and practice their computation skills. The answer: 122g. This would mean an unacceptable dilution of the milk, 2.5 mL of water for every mL of milk.

What would the answer be if we use boiling hot water of 100°C? Students calculate again, the answer is 87 g, still an unacceptable dilution. What then? What if we use steam?

Solution to Exercise 18.1

The absorbed heat by the milk is the emitted heat by the water:

With the assumption the specific heat is the same,

Equipment#

A large erlenmeyer flask

Measurement cylinder of van 100 mL

Thermometer

Cork or rubber stopper with hole

Rubber tube

Water

Burner

Heat resistant gloves (to handle the hot rubber tube) or tongs

Access to refrigerator for cold water or milk

Warning

Steam can cause bad burns. So watch out with the steam coming through the rubber tube, use insulating gloves or use tongs.

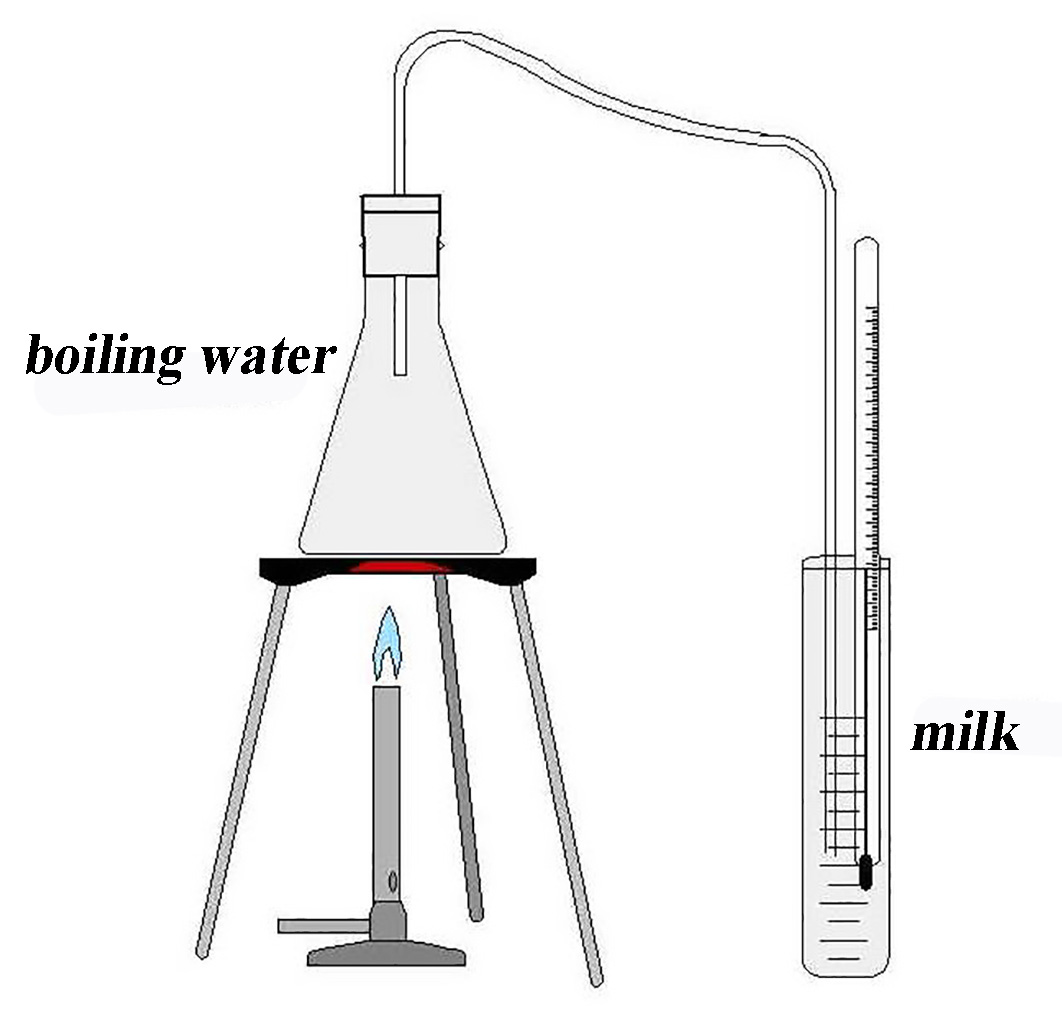

Fig. 18.2 The experimental setup#

Preparation#

Fill the Erlenmeyer with water, preferably boiling water to prevent waiting by students. Connect the rubber tube with the stopper. Fill the measuring cylinder with about 50 ml water from the refrigerator (5 ml). This water functions as “milk”. Using real milk is fine too.

Procedure#

The first part of the execution consists of calculations.

A cappuccino is made by …… (here follows the text of the introduction but without the information that a cappuccino machine uses steam)…… but what can you do if there is no time to heat the milk slowly like in a restaurant or coffee shop? A cappuccino machine adds “hot water” to heat the milk. The maximum dilution that is acceptable for the taste is 10%. Such a small dilution does not matter as espresso is strong coffee with a small amount of water.

Calculate on your worksheet how much water of 90°C has to be added to 50 ml milk of 5°C to heat it to a temperature of 65°C. Assume that the specific heat of milk equals that of water. The formulas and constants you need are on the worksheet (or on the board). (Answer 120 g).

That (120 ml) is more than 2x as much as the milk (50 ml). Suppose we use water of 100°C, how much do we need then? (Answer 86 g).

That is still more than 1.5 times more water than milk!

Suppose that water would not evaporate at 100°C. How high should be the temperature of 5 g water to be added to 50 g milk of 5°C such that the final temperature of water and milk would become 65°C? Just use the same formulas. (Answer: 665°C).

That is very high, 665°C, that is not going to work. Let’s now look at what happens if we use steam, which is what we get when we heat water above 100°C.

The teacher explains the set-up and asks a student to come to the front to measure the volume of “milk” and its temperature (should be about 5°C).

Start the experiment. Light the burner. First get the pre-heated water in the Erlenmeyer to boil. Wait until steam comes out of the rubber tube. Then put the end of the rubber tube into the “milk”. The student measurer reads the temperature every 10 seconds. Another student does general observations and is asked to look for bubbles. At about 62°C, the burner is removed. At about 65°C, the tube is removed using insulation gloves. Do not wait too long removing the tube because after turning off the burner the remaining steam will condense and reverse the flow in the tube (suction). The observer student measures the final temperature (about 65°C) and estimates how much water was added to the “milk” (about 7 g).

The milk is now 65°C and we only needed about 7 g of steam! Not 86 g! And we did not heat up to 665°C either. How is that possible, where did the energy come from?

Physics background#

The experiment clearly shows that much less steam of 100°C is needed than water of 100°C. When steam condenses to water an enormous amount of energy is released: 2256 Joules per gram steam. This energy is used to heat up the milk. This is comparable to the heat released bij cooling 665°C water to 65°C if the water would still be liquid rather than steam. A cappuccino machine uses this heat of vaporization to heat up the milk, a clever trick. That lots of energy is released is also clear from the noise. Furthermore, the machine simultaneously froths the milk. Have a nice cappuccino!

Tip

See the comment on withdrawing the tube timely from the milk before suction appears.

Worksheet

The following formulas may be of help: Specific heat:

Heat of evaporation:

In this experiment:

Attempt 1: hot water (

Calculate the amount of hot water

Answer: …

Attempt 2: boiling water (

Calculate the amount of hot water

Answer: …

Attempt 3: Very hot water

Calculate the temperature of the water,

Answer: …

Attempt 4: steam (

Calculate how much gram steam with a temperature of 100°C we need to add to 50 g ‘milk’ with a temperature of 5°C to reach a temperature of 65°C.

Answer: …

References#

- HBSVdB12

Frits Hidden, Jorn Boomsma, Anton Schins, and Ed Van den Berg. Cappuccino and specific heat versus heat of vaporization. The physics teacher, 50(2):103–104, 2012. doi:10.1119/1.3677286.