17.2. Falling faster than g#

Free fall with rotation

| Author: | Ed van den Berg |

| Time: | 5 minutes |

| Age group: | 15 and up |

| Concepts: | Acceleration of gravity g (=9.81 m/s²), free fall, rotation |

Introduction#

Everything that falls freely should experience an acceleration \(g\)? Or not? Are there exceptions? This demonstration was inspired by Ehrlich [1990].

Equipment#

Meter stick or equivalent

About 30 coins, dices or hex nuts

If possible a high-speed camera. Most phones can do 120 or 240 frames per second. Cheap action cameras can do 120 frames/second as well.

Preparation#

Think how the visibility of observations can be maximized. For example, put a chair on top of a table and use that as one of the endpoints of the meter stick. Distribute the coins more or less equally across the length of the stick.

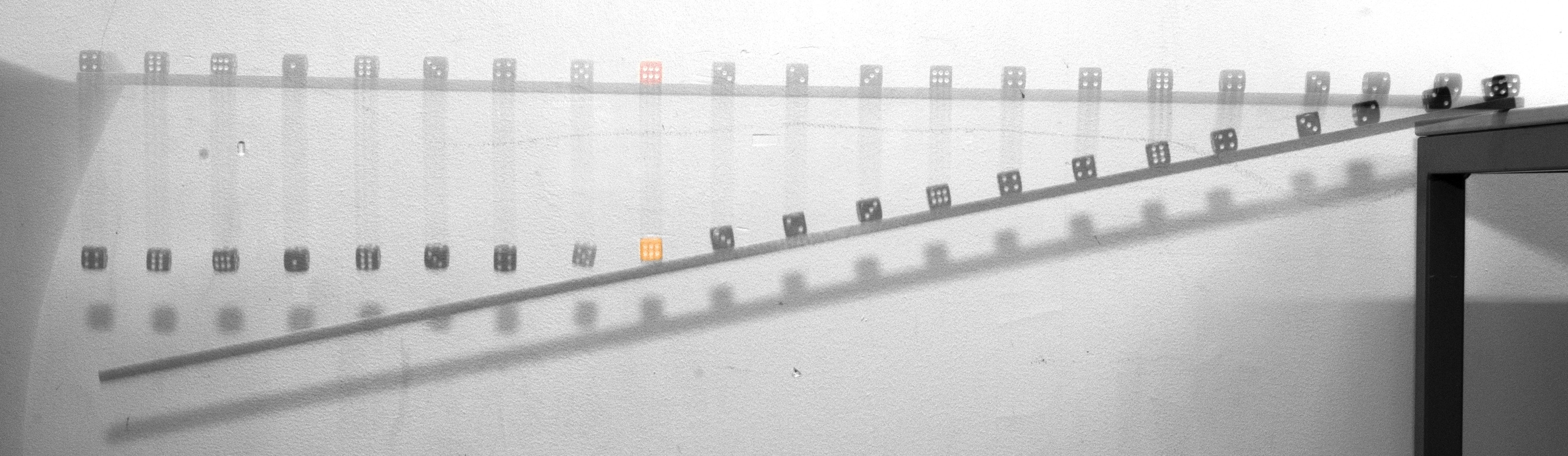

Fig. 17.3 Are some of the dices falling faster than \(g\)?#

Procedure#

You can start this demo with some simple illustrations:

Can I accelerate my hand faster than \(g\)? How can we investigate that? (Coin or stone on the hand, then pull down the hand as quick as you can).

What is free fall? Can objects in free fall be accelerated faster than g? You then turn to the actual demo.

Hold the meter stick on one end while the other side rests on the chair on top of the table (Figure 17.3).

Ask students: Suppose I let the end of the stick go, what is then the acceleration of the end? What is the acceleration of other points of the meter stick? (All points of the meter stick have the same angular acceleration, but must have a different linear acceleration as they cover different vertical distances in the same time.)

How can we investigate this with our set-up?

Let’s first keep the meter stick horizontal and drop it. Hold the stick at both ends. Will the coins keep contact with the stick? TRY! If there is a student with a mobile phone, then film with 120 or 240 frames/second.

Now put the (1m) stick with one end on the chair an holding the other end with one finger. Mark the 67 cm point but do not yet tell students why. Conduct the experiment while one of the students is recording.

It would be good to repeat and now ask students to specifically pay attention to the end of the stick.

Continue with a discussion about the linear acceleration of different points of the meter stick. This cannot be the same in rotational movement. If there are points which accelerate at less than \(g\), shouldn’t there be points that accelerate at more than \(g\)? Have we seen that?

From our observations, which points accelerate with \(g\) or less? Which points with more than %g%? The ‘tipping point’ is at 2/3 of the stick, so at 67 cm.

The physics of rotation is often not in the secondary school physics curriculum. So we will not derive theoretically that the point with acceleration \(g\) is at 2/3th of the meter stick. But we do ask our students for examples of similar phenomena. For example, a ladder which is put up too steep and turns over, a factory chimney which is blown up and falls over, a swimmer who stands on the diving board and lets himself fall over without jumping, etc.

Tip

Using the coins as indicator one can investigate shorter and longer sticks. You can move the center of mass of the stick by taping on pieces of wood in different positions. You can also conduct video measurement using your mobile phone or a high-speed camera. Students could do projects and could then study rotational physics first, for example from well known physics texts such as Young et al. [2014].

Physics background#

The moment of force (torque) on a meter stick with length \(L\) is \(\tau = \frac{mgL}{2}\). Dividing this by the rotational inertia \((1/3)mL^2\) we obtain \(\alpha = \frac{\tau}{I} = \frac{3g}{2L}\) for the angular acceleration (\(\alpha\)) (analog to \(\frac{ma}{m}\) for linear movement). The linear acceleration at a point on the stick is the product of distance from point to the rotation * angular acceleration (\(a=r\alpha\)). This will be greater than \(g\) for points farther than \(\frac{2L}{3}\).