6. Pandas#

6.1 Introduction#

With the standard Python functions and the numpy library, you already have access to powerful tools to process data. However, you’ll find that organizing data using them might still be confusing and messy… so let us introduce you to pandas: a Python library specialized in data organization. Its functions are simple to use, and they achieve a lot. Furthermore, pandas was built on top of the numpy library, using some of their functions and data structures. This makes pandas fast. The pandas library is often used in Data Science and Machine Learning to organize data that are used as input in other functions, of other libraries. For example, you store and organize an Excel file using pandas data structures, apply statistical analysis using SciPy, and then plot the result using matplotlib.

In this section, we’ll introduce you to the basic pandas data structures: the Series and DataFrame objects; and how to store data in them. In pandas, a Series represents a list, and DataFrame represents a table.

As always, let’s import some libraries. We’ll use numpy only for comparison.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

6.2 Series#

We start with pandas Series, since a DataFrame is made out of Series; retrieving a row or a column from a DataFrame results in a Series. A Series object is a numpy ndarray used to hold one-dimensional data, like a list. We create a Series object using its constructor pd.Series(). It can be called by using a list that you want to convert into a pandas series. Unlike numpy arrays, a Series may hold data of different types.

First we create a list containing elements of various types. Then we construct a Series and a numpy.array using our list. Finally we compare the type of each element in my_series and my_nparray.

my_list = ['begin', 2, 3/4, "end"]

my_series = pd.Series(data=my_list)

my_nparray = np.array(my_list)

for i in range(len(my_list)):

print('----type of each element----')

print(f'my_series element #{i} => {type(my_series[i])}')

print(f'my_nparray element #{i} => {type(my_nparray[i])}\n')

----type of each element----

my_series element #0 => <class 'str'>

my_nparray element #0 => <class 'numpy.str_'>

----type of each element----

my_series element #1 => <class 'int'>

my_nparray element #1 => <class 'numpy.str_'>

----type of each element----

my_series element #2 => <class 'float'>

my_nparray element #2 => <class 'numpy.str_'>

----type of each element----

my_series element #3 => <class 'str'>

my_nparray element #3 => <class 'numpy.str_'>

As expected, the numpy array changed all elements to one type; in this case, strings. As mentioned in Section 5.1, in Notebook 5, a numpy array cannot hold data of different types. Note that a pandas series is, by default, printed more elaborately.

print(my_series)

print('-----------------')

print(my_nparray)

0 begin

1 2

2 0.75

3 end

dtype: object

-----------------

['begin' '2' '0.75' 'end']

The values of a series can be accessed and sliced using the iloc() function:

my_series.iloc[1:]

1 2

2 0.75

3 end

dtype: object

my_series.iloc[[2,len(my_series)-1]]

2 0.75

3 end

dtype: object

Labeling Series#

So far we have referred to values within a list or array using indexing, but that might be confusing. With pandas Series, you can refer to your values by labeling their indices. Labels allow you to access the values in a more informative way, similar to dictionaries; depicted in Section 2.3, in Notebook 2.

We create the indices of the same size as the list since we want to construct our Series object with and use the index option in the Series constructor. Note that our entries can be called both ways

my_index_labels = ["My first entry", "1","2","END"]

my_labeled_Series = pd.Series(data=my_list, index=my_index_labels)

print(my_labeled_Series[0] == my_labeled_Series["My first entry"])

True

C:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\Temp\ipykernel_24848\1771852785.py:4: FutureWarning: Series.__getitem__ treating keys as positions is deprecated. In a future version, integer keys will always be treated as labels (consistent with DataFrame behavior). To access a value by position, use `ser.iloc[pos]`

print(my_labeled_Series[0] == my_labeled_Series["My first entry"])

pandas can automatically create labels of indices if we construct a Series using a dictionary with labeled entries.

my_dictionary = {"a list": [420, 10],"a float": 380/3,

"a list of strings": ["first word", "Second Word", "3rd w0rd"] }

my_Series = pd.Series(my_dictionary)

print(my_Series)

a list [420, 10]

a float 126.666667

a list of strings [first word, Second Word, 3rd w0rd]

dtype: object

We can access an element within the list labeled "a list of strings" by using its label followed by the desired index

my_Series["a list of strings"][1]

'Second Word'

Warning

When using pandas, it’s a good idea to try and avoid for loops or iterative solutions; pandas usually has a faster solution than iterating through its elements.

6.3 DataFrame#

A DataFrame is a data structure used to represent two-dimensional data. A common example of data organized in two dimensions are tables or two-dimensional arrays.

Usually, DataFrames are made out of Series. However, its constructor accepts other types.

First, we define a few series to represent individual rows with data from here.

row_1 = pd.Series(['Garnet', 7.0, 'Fracture', 3.9 ])

row_2 = pd.Series(['Graphite', 1.5, 'One', 2.3 ])

row_3 = pd.Series(['Kyanite', 6, 'One', 4.01 ])

row_4 = pd.Series(['test', 'bad', '@#$%^', False, "asdf"])

By default, the DataFrame constructor creates rows with the elements of each Series

Create DataFrame using multiple Series as rows. The name “df” is often used as a name for a dataframe object.

df2 = pd.DataFrame(data=[row_1, row_2, row_3, row_4])

df2

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Garnet | 7.0 | Fracture | 3.9 | NaN |

| 1 | Graphite | 1.5 | One | 2.3 | NaN |

| 2 | Kyanite | 6 | One | 4.01 | NaN |

| 3 | test | bad | @#$%^ | False | asdf |

We can also create a DataFrame using Series as columns:

Define series representing columns and convert each series to a dataframe.

name = pd.Series(['Amphibole', 'Biotite', 'Calcite', 'Dolomite', 'Feldspars'])

hardness = pd.Series([5.5, 2.75, 3, 3, 6])

specific_gravity = pd.Series([2.8, 3.0, 2.72, 2.85, 2.645])

test = pd.Series(['A', 12j, True, 9, 11.00000])

col_1 = name.to_frame(name='name')

col_2 = hardness.to_frame(name='hardness')

col_3 = specific_gravity.to_frame(name='sp. gr.')

col_4 = test.to_frame(name='test')

After creating each column, we can concatenate them together into one DataFrame table using the pd.concat() function. There are two axes in a DataFrame: ‘0’ (or ‘index’) for the rows, and ‘1’ (or ‘columns’) for the columns. We want to concatenate the series along their columns, so use axis=1 (or axis=’columns’).

Concatenate the series into one dataframe:

df1 = pd.concat([col_1, col_2, col_3, col_4], axis=1)

df1

| name | hardness | sp. gr. | test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Amphibole | 5.50 | 2.800 | A |

| 1 | Biotite | 2.75 | 3.000 | 12j |

| 2 | Calcite | 3.00 | 2.720 | True |

| 3 | Dolomite | 3.00 | 2.850 | 9 |

| 4 | Feldspars | 6.00 | 2.645 | 11.0 |

Alternatively, you could use the np.transpose() or .T function to generate the DataFrame using a Series as columns and then label the columns.

df_T = pd.DataFrame(data=[name,hardness,specific_gravity,test]).T

df_T.columns=['name', 'hardness', 'sp. gr.', 'test']

df_T

| name | hardness | sp. gr. | test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Amphibole | 5.5 | 2.8 | A |

| 1 | Biotite | 2.75 | 3.0 | 12j |

| 2 | Calcite | 3.0 | 2.72 | True |

| 3 | Dolomite | 3.0 | 2.85 | 9 |

| 4 | Feldspars | 6.0 | 2.645 | 11.0 |

To create a new column, simply do:

df1['new_column'] = np.nan

df1

| name | hardness | sp. gr. | test | new_column | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Amphibole | 5.50 | 2.800 | A | NaN |

| 1 | Biotite | 2.75 | 3.000 | 12j | NaN |

| 2 | Calcite | 3.00 | 2.720 | True | NaN |

| 3 | Dolomite | 3.00 | 2.850 | 9 | NaN |

| 4 | Feldspars | 6.00 | 2.645 | 11.0 | NaN |

Labeling DataFrames#

You can also rename your columns’ and rows’ index names by changing your DataFrame’s columns and index attributes, respectively. Recall our df2:

df2

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Garnet | 7.0 | Fracture | 3.9 | NaN |

| 1 | Graphite | 1.5 | One | 2.3 | NaN |

| 2 | Kyanite | 6 | One | 4.01 | NaN |

| 3 | test | bad | @#$%^ | False | asdf |

Now let’s rename its columns’ and rows’ index names.

df2.columns = ['name', 'hardness', 'cleavage', 'sp. gr.','test']

df2.index = ['row0','row1','row2','row3']

df2

| name | hardness | cleavage | sp. gr. | test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| row0 | Garnet | 7.0 | Fracture | 3.9 | NaN |

| row1 | Graphite | 1.5 | One | 2.3 | NaN |

| row2 | Kyanite | 6 | One | 4.01 | NaN |

| row3 | test | bad | @#$%^ | False | asdf |

Concatenating DataFrames#

We can also concatenate DataFrames to each other, even if they are of different sizes.

df3 = pd.concat([df1, df2])

print(df3)

name hardness sp. gr. test new_column cleavage

0 Amphibole 5.5 2.8 A NaN NaN

1 Biotite 2.75 3.0 12j NaN NaN

2 Calcite 3.0 2.72 True NaN NaN

3 Dolomite 3.0 2.85 9 NaN NaN

4 Feldspars 6.0 2.645 11.0 NaN NaN

row0 Garnet 7.0 3.9 NaN NaN Fracture

row1 Graphite 1.5 2.3 NaN NaN One

row2 Kyanite 6 4.01 NaN NaN One

row3 test bad False asdf NaN @#$%^

In the resulting table, we notice that pandas automatically added NaN (“Not a Number”) values to the missing entries of either table. Very convenient!

Removing rows and columns#

Our table looks a bit messy though… let’s make it better by removing the ’test’ row and column. We can drop them by using the pd.drop() function. By default, the pd.drop() function outputs a copy of the inserted DataFrame without the dropped items. The original data will then be preserved if you give a new name to the dataframe (i.e., the copy) with dropped items.

Example of how you could use pd.drop() to remove a row or column. Note that we used that row’s index name and column’s index name.

new_df3 = df3.drop('row3', axis=0)

new_df3 = new_df3.drop('test', axis=1)

print(new_df3)

name hardness sp. gr. new_column cleavage

0 Amphibole 5.5 2.8 NaN NaN

1 Biotite 2.75 3.0 NaN NaN

2 Calcite 3.0 2.72 NaN NaN

3 Dolomite 3.0 2.85 NaN NaN

4 Feldspars 6.0 2.645 NaN NaN

row0 Garnet 7.0 3.9 NaN Fracture

row1 Graphite 1.5 2.3 NaN One

row2 Kyanite 6 4.01 NaN One

Recall that df3 is unchanged

df3

| name | hardness | sp. gr. | test | new_column | cleavage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Amphibole | 5.5 | 2.8 | A | NaN | NaN |

| 1 | Biotite | 2.75 | 3.0 | 12j | NaN | NaN |

| 2 | Calcite | 3.0 | 2.72 | True | NaN | NaN |

| 3 | Dolomite | 3.0 | 2.85 | 9 | NaN | NaN |

| 4 | Feldspars | 6.0 | 2.645 | 11.0 | NaN | NaN |

| row0 | Garnet | 7.0 | 3.9 | NaN | NaN | Fracture |

| row1 | Graphite | 1.5 | 2.3 | NaN | NaN | One |

| row2 | Kyanite | 6 | 4.01 | NaN | NaN | One |

| row3 | test | bad | False | asdf | NaN | @#$%^ |

In case you would like to edit the original df3; you would apply the drop-operation ’inplace’. For this, we use the inplace=True option. To avoid dropping rows and columns with the same index name, you could use the pd.reset_index() function. With drop=True, the new DataFrame will have dropped the old indexes; keeping the new reset ones.

Reset the index to the default integer index and drop the old indexes.

df3_cleaned = df3.reset_index(drop=True)

df3_cleaned

| name | hardness | sp. gr. | test | new_column | cleavage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Amphibole | 5.5 | 2.8 | A | NaN | NaN |

| 1 | Biotite | 2.75 | 3.0 | 12j | NaN | NaN |

| 2 | Calcite | 3.0 | 2.72 | True | NaN | NaN |

| 3 | Dolomite | 3.0 | 2.85 | 9 | NaN | NaN |

| 4 | Feldspars | 6.0 | 2.645 | 11.0 | NaN | NaN |

| 5 | Garnet | 7.0 | 3.9 | NaN | NaN | Fracture |

| 6 | Graphite | 1.5 | 2.3 | NaN | NaN | One |

| 7 | Kyanite | 6 | 4.01 | NaN | NaN | One |

| 8 | test | bad | False | asdf | NaN | @#$%^ |

Now let’s drop row 8 and column ‘test’ (remember to add axis=1 when dropping a column).

df3_cleaned.drop(8,inplace=True)

df3_cleaned.drop('test',inplace=True, axis=1)

print(df3_cleaned)

name hardness sp. gr. new_column cleavage

0 Amphibole 5.5 2.8 NaN NaN

1 Biotite 2.75 3.0 NaN NaN

2 Calcite 3.0 2.72 NaN NaN

3 Dolomite 3.0 2.85 NaN NaN

4 Feldspars 6.0 2.645 NaN NaN

5 Garnet 7.0 3.9 NaN Fracture

6 Graphite 1.5 2.3 NaN One

7 Kyanite 6 4.01 NaN One

Note that if you try to re-run the above cell without re-running the previous one, you will get an error. This happens because after running the above cell once, you drop row ‘8’ and the ‘test’ column from df3_cleaned, trying to run again will attempt to re-drop something that doesn’t exist. Re-running the previous cell ‘fixes’ this issue since you re-assign df3_cleaned as df3.reset_index(drop=True).

Warning

If one or more rows (or columns) have the same index name, pd.drop() will drop all of them.

Accessing and modifying DataFrame values#

Now that we created our table, we want to be able to access and modify the individual values within it. This way we could add the missing values to the ’cleavage’ column. There are many ways to do this because numpy and standard Python functions are often still applicable on pandas data structures. However, there is a difference in processing speed. Therefore, when accessing or modifying data, try to use pandas functions, such as: .iat(), .at(), .iloc(), and .loc() instead of using the common [] square bracket syntax, as they might raise some warnings:

Note that the value still changed, but avoid doing so.

df3_cleaned.cleavage[1]='One'

df3_cleaned

C:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\Temp\ipykernel_24848\54782356.py:1: FutureWarning: ChainedAssignmentError: behaviour will change in pandas 3.0!

You are setting values through chained assignment. Currently this works in certain cases, but when using Copy-on-Write (which will become the default behaviour in pandas 3.0) this will never work to update the original DataFrame or Series, because the intermediate object on which we are setting values will behave as a copy.

A typical example is when you are setting values in a column of a DataFrame, like:

df["col"][row_indexer] = value

Use `df.loc[row_indexer, "col"] = values` instead, to perform the assignment in a single step and ensure this keeps updating the original `df`.

See the caveats in the documentation: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/indexing.html#returning-a-view-versus-a-copy

df3_cleaned.cleavage[1]='One'

C:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\Temp\ipykernel_24848\54782356.py:1: SettingWithCopyWarning:

A value is trying to be set on a copy of a slice from a DataFrame

See the caveats in the documentation: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/indexing.html#returning-a-view-versus-a-copy

df3_cleaned.cleavage[1]='One'

| name | hardness | sp. gr. | new_column | cleavage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Amphibole | 5.5 | 2.8 | NaN | NaN |

| 1 | Biotite | 2.75 | 3.0 | NaN | One |

| 2 | Calcite | 3.0 | 2.72 | NaN | NaN |

| 3 | Dolomite | 3.0 | 2.85 | NaN | NaN |

| 4 | Feldspars | 6.0 | 2.645 | NaN | NaN |

| 5 | Garnet | 7.0 | 3.9 | NaN | Fracture |

| 6 | Graphite | 1.5 | 2.3 | NaN | One |

| 7 | Kyanite | 6 | 4.01 | NaN | One |

.iat() vs .at() vs .iloc() vs .loc()#

In this discussion in stackoverflow, they point out some differences between these methods. To keep in mind, .iat() and .at() are the fastest ones, but they only return scalars (one element), while .loc() and .iloc() can access several elements at the same time. Lastly, .iat() and .iloc use indexes (numbers), while .at() and .loc() use labels. For more information, check the stackoverflow discussion.

Acessing values using arrays as index with .iloc(), only method that allows arrays in both rows and cols.

indx_array_row = np.array([0,1,2])

indx_array_col = np.array([0,1,2,3])

df3_cleaned.iloc[indx_array_row[:2],indx_array_col[:3]]

| name | hardness | sp. gr. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Amphibole | 5.5 | 2.8 |

| 1 | Biotite | 2.75 | 3.0 |

Accessing values with .loc(), only rows are allowed to be arrays

df3_cleaned.loc[indx_array_row[:2],'hardness']

0 5.5

1 2.75

Name: hardness, dtype: object

Or multiple columns with .loc():

df3_cleaned.loc[indx_array_row[:2],['hardness', 'cleavage']]

| hardness | cleavage | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5.5 | NaN |

| 1 | 2.75 | One |

Accessing values with .at(), no arrays allowed, only labels. Note that using 0 will work since we do not have labels for the rows so their labels are their index.

df3_cleaned.at[0, 'hardness']

5.5

If we were to change the index of this df to their names and delete column ‘name’…

df3_cleaned.index = df3_cleaned.name

df3_cleaned.drop('name',axis=1,inplace=True)

df3_cleaned

| hardness | sp. gr. | new_column | cleavage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | ||||

| Amphibole | 5.5 | 2.8 | NaN | NaN |

| Biotite | 2.75 | 3.0 | NaN | One |

| Calcite | 3.0 | 2.72 | NaN | NaN |

| Dolomite | 3.0 | 2.85 | NaN | NaN |

| Feldspars | 6.0 | 2.645 | NaN | NaN |

| Garnet | 7.0 | 3.9 | NaN | Fracture |

| Graphite | 1.5 | 2.3 | NaN | One |

| Kyanite | 6 | 4.01 | NaN | One |

Now using df.at[0,'hardness'] doesn’t work since there’s no row with label 0.

df3_cleaned.at[0, 'hardness']

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

File c:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\pypoetry\Cache\virtualenvs\learn-python-rwbttIgo-py3.11\Lib\site-packages\pandas\core\indexes\base.py:3805, in Index.get_loc(self, key)

3804 try:

-> 3805 return self._engine.get_loc(casted_key)

3806 except KeyError as err:

File index.pyx:167, in pandas._libs.index.IndexEngine.get_loc()

File index.pyx:196, in pandas._libs.index.IndexEngine.get_loc()

File pandas\\_libs\\hashtable_class_helper.pxi:7081, in pandas._libs.hashtable.PyObjectHashTable.get_item()

File pandas\\_libs\\hashtable_class_helper.pxi:7089, in pandas._libs.hashtable.PyObjectHashTable.get_item()

KeyError: 0

The above exception was the direct cause of the following exception:

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[58], line 1

----> 1 df3_cleaned.at[0, 'hardness']

File c:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\pypoetry\Cache\virtualenvs\learn-python-rwbttIgo-py3.11\Lib\site-packages\pandas\core\indexing.py:2575, in _AtIndexer.__getitem__(self, key)

2572 raise ValueError("Invalid call for scalar access (getting)!")

2573 return self.obj.loc[key]

-> 2575 return super().__getitem__(key)

File c:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\pypoetry\Cache\virtualenvs\learn-python-rwbttIgo-py3.11\Lib\site-packages\pandas\core\indexing.py:2527, in _ScalarAccessIndexer.__getitem__(self, key)

2524 raise ValueError("Invalid call for scalar access (getting)!")

2526 key = self._convert_key(key)

-> 2527 return self.obj._get_value(*key, takeable=self._takeable)

File c:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\pypoetry\Cache\virtualenvs\learn-python-rwbttIgo-py3.11\Lib\site-packages\pandas\core\frame.py:4209, in DataFrame._get_value(self, index, col, takeable)

4203 engine = self.index._engine

4205 if not isinstance(self.index, MultiIndex):

4206 # CategoricalIndex: Trying to use the engine fastpath may give incorrect

4207 # results if our categories are integers that dont match our codes

4208 # IntervalIndex: IntervalTree has no get_loc

-> 4209 row = self.index.get_loc(index)

4210 return series._values[row]

4212 # For MultiIndex going through engine effectively restricts us to

4213 # same-length tuples; see test_get_set_value_no_partial_indexing

File c:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\pypoetry\Cache\virtualenvs\learn-python-rwbttIgo-py3.11\Lib\site-packages\pandas\core\indexes\base.py:3812, in Index.get_loc(self, key)

3807 if isinstance(casted_key, slice) or (

3808 isinstance(casted_key, abc.Iterable)

3809 and any(isinstance(x, slice) for x in casted_key)

3810 ):

3811 raise InvalidIndexError(key)

-> 3812 raise KeyError(key) from err

3813 except TypeError:

3814 # If we have a listlike key, _check_indexing_error will raise

3815 # InvalidIndexError. Otherwise we fall through and re-raise

3816 # the TypeError.

3817 self._check_indexing_error(key)

KeyError: 0

Accessing values with .iat(), no arrays allowed, no labels allowed only indexes.

df3_cleaned.iat[1, 2]

nan

In case you want to know the index number of a column or row:

print(df3_cleaned.columns.get_loc('new_column'))

print(df3_cleaned.index.get_loc('Dolomite'))

2

3

Since the above lines return the index of a column and row you can use them directly with .iat().

df3_cleaned.iat[df3_cleaned.index.get_loc('Dolomite'), df3_cleaned.columns.get_loc('new_column')]

nan

Selecting multiple columns:

df3_cleaned[['hardness','new_column']]

| hardness | new_column | |

|---|---|---|

| name | ||

| Amphibole | 5.5 | NaN |

| Biotite | 2.75 | NaN |

| Calcite | 3.0 | NaN |

| Dolomite | 3.0 | NaN |

| Feldspars | 6.0 | NaN |

| Garnet | 7.0 | NaN |

| Graphite | 1.5 | NaN |

| Kyanite | 6 | NaN |

Finally, removing a column by making a copy and re-assigning the original variable as its copy. (Alternative to inplace=True)

df3_cleaned = df3_cleaned.drop('new_column', axis=1)

df3_cleaned

| hardness | sp. gr. | cleavage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| name | |||

| Amphibole | 5.5 | 2.8 | NaN |

| Biotite | 2.75 | 3.0 | One |

| Calcite | 3.0 | 2.72 | NaN |

| Dolomite | 3.0 | 2.85 | NaN |

| Feldspars | 6.0 | 2.645 | NaN |

| Garnet | 7.0 | 3.9 | Fracture |

| Graphite | 1.5 | 2.3 | One |

| Kyanite | 6 | 4.01 | One |

6.4 Importing data into DataFrames and exploring its attributes#

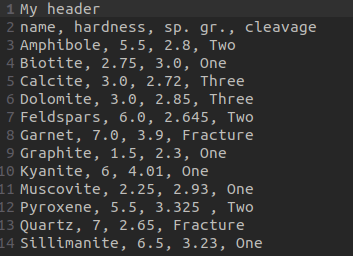

pandas provides many functions to import data into dataframes, such as read_csv() to read delimited text files, or read_excel() for Excel or OpenDocument spreadsheets. read_csv() provides options that allow you to filter the data, such as specifying the separator/delimiter, the lines that form the headers, which rows to skip, etc. Let’s analyze the mineral_properties.txt. Below a screenshot of it:

below we import the .txt:

we indicate that the separator is the comma

"sep=','"we indicate the header (what should be the columns names) is in the second line

"header=[1]"we indicate to not skip any rows

"skiprows=None"we indicate the first column should be the index of the rows

"index_col=0"

file_location = ("mineral_properties.txt")

df4 = pd.read_csv(file_location, sep=',', header=[1],

skiprows=None, index_col=0)

df4

| hardness | sp. gr. | cleavage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| name | |||

| Amphibole | 5.50 | 2.800 | Two |

| Biotite | 2.75 | 3.000 | One |

| Calcite | 3.00 | 2.720 | Three |

| Dolomite | 3.00 | 2.850 | Three |

| Feldspars | 6.00 | 2.645 | Two |

| Garnet | 7.00 | 3.900 | Fracture |

| Graphite | 1.50 | 2.300 | One |

| Kyanite | 6.00 | 4.010 | One |

| Muscovite | 2.25 | 2.930 | One |

| Pyroxene | 5.50 | 3.325 | Two |

| Quartz | 7.00 | 2.650 | Fracture |

| Sillimanite | 6.50 | 3.230 | One |

Note that if we try to call any of the columns from df4 we will get an error.

df4['hardness']

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

File c:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\pypoetry\Cache\virtualenvs\learn-python-rwbttIgo-py3.11\Lib\site-packages\pandas\core\indexes\base.py:3805, in Index.get_loc(self, key)

3804 try:

-> 3805 return self._engine.get_loc(casted_key)

3806 except KeyError as err:

File index.pyx:167, in pandas._libs.index.IndexEngine.get_loc()

File index.pyx:196, in pandas._libs.index.IndexEngine.get_loc()

File pandas\\_libs\\hashtable_class_helper.pxi:7081, in pandas._libs.hashtable.PyObjectHashTable.get_item()

File pandas\\_libs\\hashtable_class_helper.pxi:7089, in pandas._libs.hashtable.PyObjectHashTable.get_item()

KeyError: 'hardness'

The above exception was the direct cause of the following exception:

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[67], line 1

----> 1 df4['hardness']

File c:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\pypoetry\Cache\virtualenvs\learn-python-rwbttIgo-py3.11\Lib\site-packages\pandas\core\frame.py:4090, in DataFrame.__getitem__(self, key)

4088 if self.columns.nlevels > 1:

4089 return self._getitem_multilevel(key)

-> 4090 indexer = self.columns.get_loc(key)

4091 if is_integer(indexer):

4092 indexer = [indexer]

File c:\Users\gui-win10\AppData\Local\pypoetry\Cache\virtualenvs\learn-python-rwbttIgo-py3.11\Lib\site-packages\pandas\core\indexes\base.py:3812, in Index.get_loc(self, key)

3807 if isinstance(casted_key, slice) or (

3808 isinstance(casted_key, abc.Iterable)

3809 and any(isinstance(x, slice) for x in casted_key)

3810 ):

3811 raise InvalidIndexError(key)

-> 3812 raise KeyError(key) from err

3813 except TypeError:

3814 # If we have a listlike key, _check_indexing_error will raise

3815 # InvalidIndexError. Otherwise we fall through and re-raise

3816 # the TypeError.

3817 self._check_indexing_error(key)

KeyError: 'hardness'

Do you know why?

Answer …

In case you were not able to answer the above question, let’s look into df4.columns

df4.columns

Index([' hardness', ' sp. gr.', ' cleavage'], dtype='object')

You see there are spaces at the beginning of each column name… this happens because that’s how people usually type, with commas followed by a space. We could use the skipinitialspace = True from the pd.read_csv() function to avoid this. Let’s try it out:

df4 = pd.read_csv(file_location + 'mineral_properties.txt',sep=',',header=[1],

skiprows=None, index_col=0, skipinitialspace=True)

print(df4.columns)

Index(['hardness', 'sp. gr.', 'cleavage'], dtype='object')

Ok, much better!

6.5 Statistics with pandas#

Recall some functions such as np.mean() and np.max(); these functions can be used to calculate a row’s or column’s statistics. Say you want to know what’s the average hardness of the different minerals:

df4['hardness'].mean()

4.666666666666667

Often we don’t know much about the data, and printing all the values is inconvenient. In that case, it’s wise to take a look at some of its attributes first.

See the labels of the columns and rows.

print(df4.columns)

print('----------------------')

print(df4.index)

Index(['hardness', 'sp. gr.', 'cleavage'], dtype='object')

----------------------

Index(['Amphibole', 'Biotite', 'Calcite', 'Dolomite', 'Feldspars', 'Garnet',

'Graphite', 'Kyanite', 'Muscovite', 'Pyroxene', 'Quartz',

'Sillimanite'],

dtype='object', name='name')

df4.info is similar to print(df4.info).

df4.info

<bound method DataFrame.info of hardness sp. gr. cleavage

name

Amphibole 5.50 2.800 Two

Biotite 2.75 3.000 One

Calcite 3.00 2.720 Three

Dolomite 3.00 2.850 Three

Feldspars 6.00 2.645 Two

Garnet 7.00 3.900 Fracture

Graphite 1.50 2.300 One

Kyanite 6.00 4.010 One

Muscovite 2.25 2.930 One

Pyroxene 5.50 3.325 Two

Quartz 7.00 2.650 Fracture

Sillimanite 6.50 3.230 One>

Deep copying a DataFrame#

As you have seen in Notebook 4, shallow copies can be troublesome if you’re not aware of it. In pandas, it’s the same story.

To make a deep copy use the DataFrame.copy(deep=True) function.

df_deep = df4.copy(deep=True)

Now, altering df_deep will not alter df4; and vice-versa.

Additional study material:#

After this Notebook you should be able to:

understand

SeriesandDataFramesconcatenate

DataFrameswork with different labels of a

DataFramedrop unwanted rows and columns

access and modify values within your

DataFrameimport data into a

pandas DataFramemanipulate a

DataFramein several important ways